History Lessons: Breaking the Endless Cycle of Market Rigging

Major new study reveals the 25 types of financial misconduct that have proved timeless and repetitive.

In 1905, Spanish philosopher George Santayana said those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it, and in 2018 an exhaustive study of misconduct in financial markets has proved just that; it describes the same 25 patterns of bad behaviour that have been consistently recurring for the last 225 years in capital markets.

The Behavioural Cluster Analysis (BCA) was published by the FICC Market Standards Board (FMSB). The FMSB was created in 2015 following multiple conduct debacles such as Libor, and is the result of the study of 390 cases of attempted market manipulation since 1792, in an attempt to identify the core behaviours that occur most frequently.

“We pulled together a database of all cases of market manipulation we could find; hundreds and hundreds of cases,” said FSMB chairman Mark Yallop. “The first was in 1792, which involved manipulation of the US bond market, where the perpetrator squeezed it with a group of co-conspirators and ended up dying in prison years later. That was followed by multiple other examples, up to the more recent cases with Bitcoin.”

The team looked at 26 different jurisdictions beginning with the US and UK, and were astonished, Yallop said, to find the same patterns appearing.

“We found there were not hundreds or thousands of different ways of market manipulation, just a few techniques which people have copied, transferred from markets,” he said. “So what appeared in the commodities market was copied over to the rates market, into the credit and equities markets. What happened in the US then happened in Europe. What happened in voice markets later happened in electronic markets as the structure evolved.”

According to the FMSB, the report’s purpose is practical: identifying the relevant behaviours that result in market misconduct is an essential step to forestalling them.

A team at the City law firm, Macfarlanes, worked with the FMSB on the project, and Dan Lavender, a partner there who is co-author of the report, said that it was clear the same behaviours bubbled up again and again. “We think the BCA will be a valuable resource for financial market participants and their advisors,” he said. “It is a practical document and we hope it will become a useful reference point for financial services firms.”

There will be no penalties or regulatory enforcements initiated as a result of the findings, but it is hoped the behaviours in question, now illustrated so definitively, can be understood by market participants, and regulators, and factored into their systems and control frameworks.

Remarkably it is the first time that these patterns of behaviour have been collated, analysed and published as a single reference point for market participants.

“It is encouraging, and slightly staggering, to think that over two centuries’ worth of market misconduct and manipulation has been boiled down to 25 behavioural patterns we need to combat,” said Karim Haji, head of banking, KPMG UK and member of the FMSB Advisory Council.”

Despite reams of data on current and past transgressions, predicting the future when it comes to rogue trading seemingly amounts to little more than guesswork.

“It has shown, for the first time, there are not an infinite number of ways of manipulating markets,” said Yallop. “And that means for a firm worried about trying to control risks, supervise staff and trading activity, you do not have to worry about every single thing that can go wrong, just focus on these 25 specific techniques, build systems and processes that will enable you to watch out for these patterns of behaviour, because those are where the problems will arise.”

The analysis suggests these patterns are not only recurrent over time but even evolve to work within new technologies and new forms of communication. The same types of misconduct and patterns occur across different jurisdictions and countries, showing little deviation by geographical boundary, and are not specific to any particular asset class or market structure.

Of the 25 patterns, the report’s authors grouped them into seven broad categories: Price Manipulation; Circular Trading; Collusion & Information Sharing; Inside Information; Reference Price Influence; Improper Order Handling; Misleading Customers.

Shady business around cryptocurrency is the most recent phenomenon, but as the paper points out, fraudulent behaviour involving ‘wash trades’ has been around almost as long as securities have been traded.

A ‘wash’ typically involves a purchase and sale of securities that match in price, size and time of execution, with no change in beneficial ownership or transfer of risk. There are a number of variations of wash trades, which can be used in combination with others to advance different manipulative techniques. In these circumstances, wash trades, matched orders and matched trades are frequently described simply as collusive trading or pre-arranged trading.

A vivid example comes from misconduct evidenced in a 2015 action by the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission against the Bitcoin swap facility TeraExchange, in which the firm was found to be misrepresenting trading activity to the public; this echoes a 1935 case study where the president and controlling shareholder of Manhattan Electrical Supply Co. were involved in a scheme to artificially inflate the price of the company’s shares.

Brokers were paid to recommend the stock and conduct ‘washing’ sales, made possible by the numerous accounts controlled by the actors between whom transactions could be executed and then cancelled. They ramped the price to $55 in May 1930. Trading in the stock was suspended for several days after which the stock opened below $20 and never recovered.

The paper also looks at ‘Bull and Bear Raiding’, the practice of spreading false rumours in order to move a price advantageous to that party. The dissemination of false information, now billed as “fake news,” is a consistent feature of the cluster as observed through history, and several variations have arisen over time as new media have been developed.

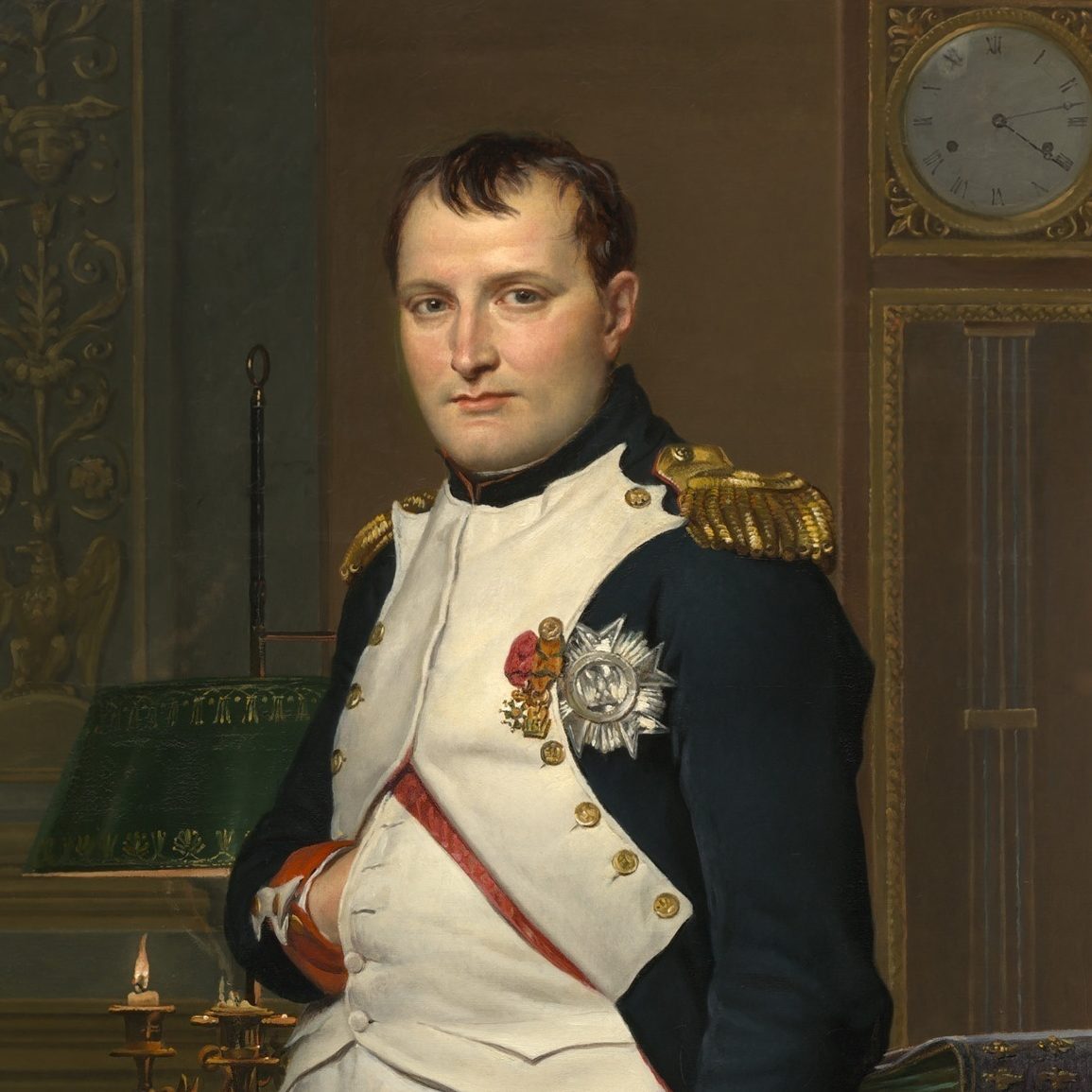

In 1814, a conspiracy was formulated to profit from the publication of false information that Napoleon Bonaparte had been killed. Having accumulated a large position in UK government bonds, Captain Charles De Berenger appeared in the port of Dover, Kent, disguised as a Bourbon Officer and calling himself Lieutenant Colonel Du Bourg.

He reported that Napoleon had been killed by the Prussians and sent a false letter to that effect to the Port Admiral at Deal for transmission to the Admiralty in London by telegraph, which was expected to be published in the press.

Co-conspirators paraded across London Bridge proclaiming an allied victory and distributing handbills to that effect. The price of UK government bonds rose on the news, leading the syndicate to sell the bonds they had purchased prior to the bull raid on the London market.

It is a familiar story today, as financial markets are roiled by fake news emanating from social media and politically-motivated alternative news platforms.

Tesla and its maverick CEO Elon Musk were recently charged by the SEC over allegations that Musk committed fraud when he said he had secured the funding needed to take Tesla private via a Tweet, prompting the car marker’s share price to plummet. This all stemmed from an off-hand, unthoughtful social media update.

US regulators have sounded the alarm over online paid stock-promotion campaigns, and the Turkish Lira also plummeted over the summer, partly driven by questionable online posts.

The US Financial Industry Regulatory Authority told Radar that it is concerned stocks are being ramped and manipulated via fake accounts on Twitter and Facebook, with the backdrop of Big Data becoming more readily accessible for cyber-criminals as well as for everyday use by corporates.

The next challenge is for firms to mine the data uncovered in the FMSB report and use it to tweak their lexicons or work it into their monitoring and surveillance systems. There is certainly no question of its importance and if combined with modern behavioural analytics software, there is a real opportunity for firms to deliver compliance that offers more than box-ticking appeasement for regulators and internal audit.

“Markets have to operate effectively, fairly and honestly, the findings of the FMSB’s analysis marks a major step towards this end, we now have a better way to manage misconduct risk, we have to make sure it is used,” said Haji.

On human nature, Santayana also said: “Only the dead have seen the end of war,” which would seem to suggest that he felt even those who do read history are still not free from the mistakes of the past.

It would be naive to think the capital markets sector can entirely rid itself of attempts to cheat the system, but the study does give firms the best chance yet of rooting out the behaviours that lead to market misconduct before they make the headlines in the Wall Street Journal, again.